|

| December 26, 2012 | Volume 08 Issue 48 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Lightning in a bottle:

Army engineers set phasers to 'fry'

By Jason Kaneshiro, AMC

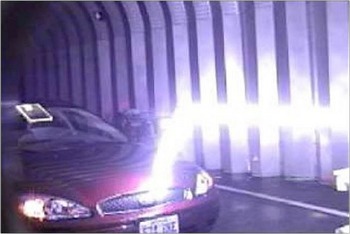

A guided lightning bolt travels horizontally, then hits a car when it finds the lower resistance path to ground. The lightning is guided in a laser-induced plasma channel, then it deviates from the channel when it gets close to the target and has a lower resistance path to ground. Picatinny Arsenal engineers believe the technology holds great promise. [U.S. Army photo]

Scientists and engineers at Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey are busy developing a device that will shoot lightning bolts down laser beams to destroy its target.

Soldiers and science fiction fans ... you are welcome.

"We never got tired of the lightning bolts zapping our simulated (targets)," says George Fischer, lead scientist on the project.

The Laser-Induced Plasma Channel, or LIPC, is designed to take out targets that conduct electricity better than the air or ground that surrounds them. How did the scientists harness the seemingly random path made by lightning bolts, and how does a laser help? To understand how the technology works, it helps to get a brief background on physics.

"Light travels more slowly in gases and solids than it does in a vacuum," says Fischer. "We typically think of the speed of light in each material as constant. There is, however, a very small additional intensity-dependent factor to its speed. In air, this factor is positive, so light slows down by a tiny fraction when the light is more intense."

"If a laser puts out a pulse with modest energy, but the time is incredibly tiny, the power can be huge," Fischer continued. "During the duration of the laser pulse, it can be putting out more power than a large city needs, but the pulse only lasts for two-trillionths of a second."

Why is this important?

"For very powerful and high-intensity laser pulses, the air can act like a lens, keeping the light in a small-diameter filament," says Fischer. "We use an ultra-short-pulse laser of modest energy to make a laser beam so intense that it focuses on itself in air and stays focused in a filament."

To put the energy output in perspective, a big filament light bulb uses 100 W. The optical amplifier output is 50 billion W of optical power, Fischer says.

"If a laser beam is intense enough, its electro-magnetic field is strong enough to rip electrons off of air molecules, creating plasma," says Fischer. "This plasma is located along the path of the laser beam, so we can direct it wherever we want by moving a mirror."

"Air is composed of neutral molecules and is an insulator," Fischer says. When lightning from a thunderstorm leaps from cloud to ground, it behaves just as any other sources of electrical energy and follows the path of least resistance.

"The plasma channel conducts electricity way better than un-ionized air, so if we set up the laser so that the filament comes near a high-voltage source, the electrical energy will travel down the filament," Fischer says.

A target, an enemy vehicle, or even some types of unexploded ordnance would be a better conductor than the ground it sits on. Since the voltage drop across the target would be the same as the voltage drop across the same distance of ground, current flows through the target. In the case of unexploded ordnance, it would detonate, explains Fischer.

Even though the physics behind the project is sound, the technical challenges were many, Fischer recalls.

"If the light focuses in air, there is certainly the danger that it will focus in a glass lens, or in other parts of the laser amplifier system, destroying it," Fischer says. "We needed to lower the intensity in the optical amplifier and keep it low until we wanted the light to self-focus in air."

Other challenges included synchronizing the laser with the high voltage, ruggedizing the device to survive under the extreme environmental conditions of an operational environment, and powering the system for extended periods of time.

"There are a number of high-tech components that need to run continuously," says Fischer.

But despite the challenges, the project has made notable progress in recent months.

"Definitely our last week of testing in January 2012 was a highlight," says Tom Shadis, project officer on the program. "We had a well-thought-out test plan, and our ARDEC and contractor team worked together tirelessly and efficiently over long hours to work through the entire plan.

"The excellent results certainly added to the excitement and camaraderie," Fischer says.

As development continues, Shadis said that those involved with the project never lose sight of the importance of their work.

"We were all proud to be serving our warfighters and can picture the LIPC system saving U.S. lives," Fischer says.

Published July 2012

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy